Memory is a bottleneck.

-

Driven by the excessive demands of modern workloads, the evolution of memory technologies increasingly prioritizes bandwidth and capacity over access latency, and this is a big issue.

-

One way to hide this memory latency is to prefetch.

-

Prefetching refers to the act of predicting subsequent memory accesses and fetching the required data ahead of the processor execution.

To Achieve this, A prefetcher needs to manage training metadata, learned memory access patterns and control metadata.

We assess the effectiveness of prefetchers using the following metrics:

- Accuracy: Accuracy indicates the correctness of the prefetch actions performed by the prefetcher.

- Coverage: Coverage measures the prefetcher’s ability to detect the access patterns of a program.

Issues with Conventional Prefetchers

In view of the high-bandwidth, high-capacity memory trends, we believe it is essential to harness memory as an important component in prefetcher architectures. Therefore, we categorize hardware prefetchers into two groups: those who can leverage off-chip memory, and those who don’t.

-

Temporal Prefetchers

- they focus on irregular access patterns.

- For instance, ISB [14], MISB [15], and STMS [16] record streams of past cache misses and issue prefetches by replaying a stream when the identical leading access address appears again.

- Although they successfully out-source the storage of long streams and can tolerate high latency, temporal prefetchers can only support a specific class of applications.

- This is because they require exact access sequence repetition to work, which are only seen in programs with pointer-rich data references [32, 33] or complex instruction control flow [34–38].

-

Spatial Prefetchers

- Spatial prefetchers have a remarkable strength of eliminating compulsory cache misses.

- Compulsory cache misses are a major source of performance degradation in important classes of applications.

- An application exhibits spatial correlation because its data objects or groups of data objects often share a same data structure and the same memory layout thereof.

- The bit-vector-based prefetching represents an important form of spatial data prefetchers. It learns access patterns of memory regions at the granularity of a fixed size, e.g. 4 KB pages.

RICH: Design Philosophy

There are two key aspects:

- identify the opportunity arising from the memory technology trends and leverage more predictor metadata to boost prefetching performance.

- address the challenge of minimizing the overheads of the new metadata by wise use of off-chip and on-chip resources altogether.

Insight No.1

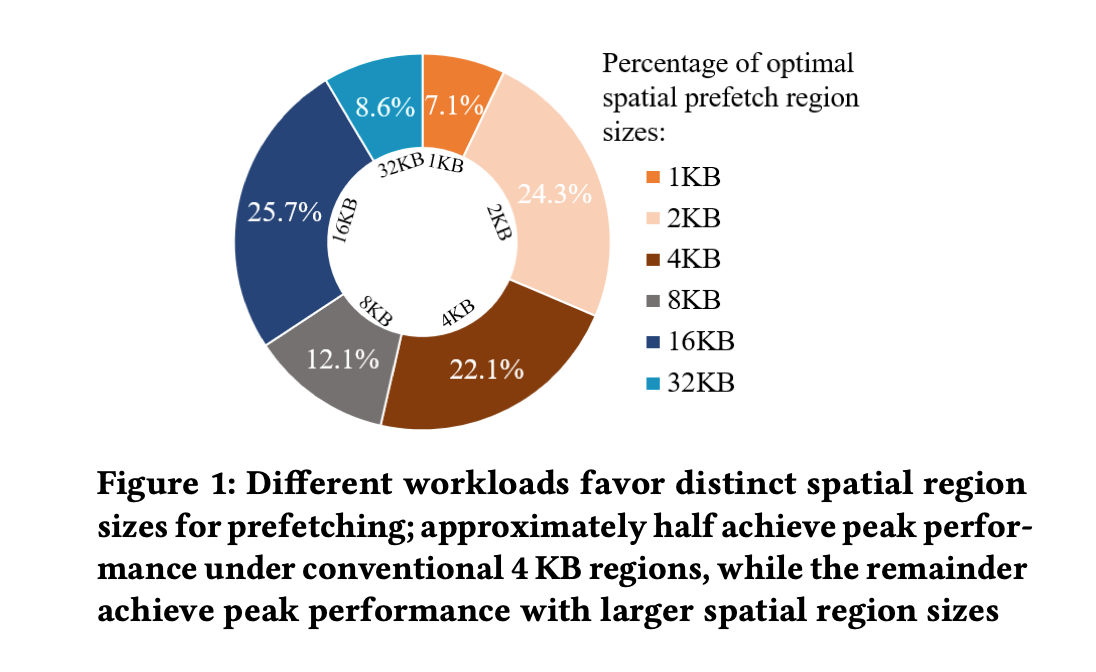

Workloads prefer diverse region sizes for spatial prefetching.

e.g., half of them work best under conventional 4 KB sizes, while the other half prefer larger ones. Therefore, supporting multiple region sizes is crucial for performance.

- As illustrated in Figure 1, different traces reach their highest performance at different region sizes, with 46% of the samples peak when the region size is set larger than 4 KB.

RICH: High-Level Idea

- Conventional prefetchers are fundamentally constrained by on-chip storage: to keep lookup latency small, they are forced to store only a tiny amount of metadata close to the core.

- RICH instead treats main memory itself as a scalable backing store for prefetch metadata and only keeps a compact “cache” of hot metadata entries on-chip.

- Each region of memory has an associated metadata record that captures which cache lines inside the region tend to be accessed together; this is the basis for spatial correlation.

- By allowing far more metadata than fits on-chip, RICH can learn richer, longer-lived spatial patterns without throwing old information away as aggressively.

RICH: Metadata Organization

- RICH partitions the physical address space into regions and allows multiple region sizes, so that an application that prefers fine-grain correlation can use small regions, while streaming or array-based codes can use larger ones.

- For each active region, RICH keeps:

- A region descriptor (region base, region size, and a few control bits).

- A compact bit-vector (or similar structure) that records which cache lines in the region have been seen and which lines should be prefetched when a particular line is accessed.

- These region metadata records predominantly live in off-chip memory, in a dedicated metadata area; an on-chip structure only caches the most recently used ones to keep lookup latency low.

- When a region’s metadata is not present on-chip, RICH issues a metadata fetch to memory, then uses and updates it just like a regular cached entry.

RICH: Prefetching Workflow

On every qualifying cache miss (typically at the last-level cache), RICH performs three main steps:

- Region lookup

- Compute the region that contains the missed address (taking the current region-size choice into account).

- Probe the on-chip RICH metadata cache; on a miss there, fetch the region’s metadata from memory.

- Prefetch decision

- Use the region’s bit-vector to find lines that are strongly correlated with the current miss.

- Filter out lines that are already present or are too far ahead to be useful, then issue prefetch requests for the remaining candidates.

- Training / update

- Once the demand access is resolved, update the region metadata to reflect the new access.

- If the metadata record has been modified, write it back lazily to memory so that future references (even on a different core) can reuse the learned pattern.

Trading Memory for Latency Hiding

- Using main memory to store most of the metadata increases access latency for cold regions, but this is acceptable because:

- Prefetch requests are inherently latency-tolerant, and

- The on-chip cache filters most hot regions, so common cases still see low metadata lookup latency.

- The extra memory footprint is modest relative to DRAM capacity but enables much richer spatial models than purely on-chip designs.

- Compared to conventional spatial prefetchers that use a fixed, small table, RICH significantly improves:

- Coverage, by tracking more regions and longer execution histories.

- Accuracy, by adapting region sizes and keeping per-region correlation information instead of coarse global patterns.

Qualitative Benefits and Limitations

- Strengths

- Particularly effective for workloads with structured but non-uniform spatial locality (e.g., graph analytics, irregular scientific codes, and some server workloads).

- Naturally complements temporal prefetchers: RICH focuses on spatial correlations within regions, while temporal prefetchers capture repeating miss sequences.

- Scales with memory capacity: as DRAM sizes grow, the system can afford more and richer metadata.

- Costs / caveats

- Consumes extra DRAM capacity and bandwidth for metadata accesses, which can become noticeable on memory-bandwidth-bound systems.

- Less useful when workloads have very little spatial locality or when access patterns change too rapidly for metadata to be reused.

- Requires careful hardware implementation to ensure that metadata fetches and writebacks do not interfere with critical demand traffic.

Implementation Notes

- Placement in the memory hierarchy

- RICH is typically implemented at or near the last-level cache (LLC) so it can observe all misses and issue prefetches toward memory.

- The on-chip metadata cache sits alongside the LLC tags and data, but is much smaller than the full off-chip metadata space.

- Metadata address mapping

- Each physical region is mapped to a metadata entry using a deterministic function (e.g., hashing the region base) so that metadata can be located in DRAM without extra tags.

- A fixed area of DRAM is reserved for metadata, and the memory controller knows how to translate a region identifier into a DRAM address for the metadata record.

- On-chip structures

- The RICH metadata cache can be implemented as a set-associative structure with LRU or a simple replacement policy, similar to a small cache.

- A small queue or buffer may be used to track outstanding metadata fetches and writebacks, decoupling them from critical data requests.

- Interaction with the memory controller

- Metadata reads and writebacks are scheduled with lower priority than demand loads/stores to avoid harming critical-path latency.

- Simple throttling logic can limit the number of in-flight metadata operations when the memory system is heavily loaded.

- Coherence and sharing

- Since metadata is advisory (it does not affect correctness), it does not need strict cache-coherence; stale metadata at worst leads to useless or missed prefetches.

- In multicore systems, cores can either share a global RICH metadata space or keep per-core partitions, depending on area and complexity budgets.

- Fallback behavior

- If metadata is not available in time (e.g., due to a long metadata miss), the prefetcher can simply skip issuing prefetches for that access.

- When RICH is disabled or bypassed, the system falls back to baseline behavior with no impact on correctness.